State doesn’t misuse funds from license sales to hunters, anglers

By SHANNON TOMPKINS

Copyright 2011 Houston Chronicle

Aug. 14, 2011, 8:03PM

Texas hunters and anglers begin a pair of annual rituals Monday - purchasing new hunting/fishing licenses and grumbling about how the state “steals” part of that license revenue.

There’s no way around the first part of the ritual; all current Texas hunting licenses and most fishing licenses expire Aug. 31, and new 2011-12 licenses, which become available for purchase Monday, are required on Sept. 1.

But that second ritual is a bit of misguided, or at least misdirected, animosity arising from the license-buying public’s understandable misunderstanding of the Byzantine budget maneuvers the Texas Legislature uses to produce its constitutionally mandated balanced budget.

The common belief is that part of the approximately $90 million Texas hunters and anglers pay annually for the more than 2 million licenses is siphoned out of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department coffers and used to finance unrelated state programs. This is a persistent myth.

Not a cent of fishing or hunting license fees goes into the state’s General Revenue Fund or other accounts used to pay for non-outdoors-related state programs or services. All of it goes directly into the Game, Fish and Water Safety Fund — officially, Fund 9 – which, by law, can be used only to fund TPWD programs.

But that’s not to say Texas’ hunters and anglers, its wildlife and fisheries resources and the agency charged with managing them aren’t shortchanged when it comes to how license revenue is spent – or, more correctly, not spent.

Stagnant money

Every year, tens of millions of dollars in hunting and fishing license fees are left sitting in the state account used to fund Texas wildlife, fisheries and boating programs. Those millions of dollars in Fund 9 account balances – $31 million at the end of this month, jumping to an estimated $48 million this time next year and as much as $64 million by Aug. 31, 2013 – are there because the Legislature holds those millions hostage in the scheme used to produce, on paper at least, the balanced budget that it is required to fashion.

Here’s how it works: Thanks to far-sighted federal lawmakers, state hunting and fishing license money is protected from being spent for anything other than funding wildlife, fisheries and boating programs.

Two federal programs – Sport Fish Restoration and Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration, more commonly called, Dingell-Johnson/Wallop-Breaux Acts and Pittman-Robertson Act for their congressional sponsors – collect federal excise taxes on equipment used for hunting, shooting, fishing and other outdoor recreation.

Those federal excise taxes are distributed to the states to help fund state-run wildlife and fisheries programs and research projects. Texas gets about $40 million a year from these federal fisheries and wildlife programs.

But Congress was smart when it drafted the excise tax disbursement laws. For a state to qualify to receive the federal funds, it must pass a state law prohibiting using hunting and fishing license revenue for anything other than wildlife and fisheries programs.

If a state legislature dips into hunting and fishing license accounts to pay for, say, roads or hospitals or any other program, the state stands to lose all of its federal excise tax reimbursements.

So, as much as the Texas Legislature might be tempted to stick its hands into a flush Fund 9, particularly in times such as these when the state faces crippling general-revenue shortfalls, the prospect of losing that $40 million in federal money is incentive enough to prevent such plundering.

But the Legislature has found other ways of using that Fund 9 money without actually spending it.

Good on paper

For TPWD to spend money from the Fund 9 pot, that money has to be appropriated by the Legislature through its budget and appropriations acts.

By appropriating only some of the license money, the Legislature can count the “unappropriated balance” in Fund 9 on the positive side of the ledger when calculating the overall state budget.

This tactic is not restricted to hunting and fishing license revenue. It happens with revenue generated from the sale of vehicle license plates (horned toad, bluebonnet, etc.) benefiting state parks, wildlife, hunting and freshwater fishing.

All of these “unappropriated balances” – money Texans spent believing all of the dollars would be used to fund programs they voluntarily support by paying additional fees for the specialized license plates – are rat-holed and left dormant in accounts as a way to offset negative balances in other state programs.

The amount of Fund 9 money left unappropriated is highest in tough economic times such as the state currently faces, and less when the state economy is healthy. And when economic conditions improve, the Legislature allows TPWD to spend some of the balance that has built up over tough years.

Money that Texas hunters and anglers paid for their licenses, along with those federal excise tax reimbursements, wholly fund TPWD’s wildlife, inland fisheries and coastal fisheries divisions. As a result of the Legislature’s increase in the unappropriated balances in Fund 9 and other “dedicated” TPWD funds in budgets for the next two fiscal years, the agency is being forced to cut back on fisheries and wildlife management programs that benefit the state’s natural resources as well as hunters, anglers, boaters, and others who enjoy the state’s outdoors.

And it has had a human cost. Facing severe budget cuts for the coming two years, TPWD laid off 115 employees over the past month. Those layoffs included 9 percent of the staff in the agency’s wildlife division, 8 percent of the inland fisheries division and just under 3 percent of the coastal fisheries division.

No, the Texas Legislature doesn’t pilfer hunters’ and anglers’ license dollars and spend them on other programs. It just doesn’t spend them at all. And that’s almost as bad.

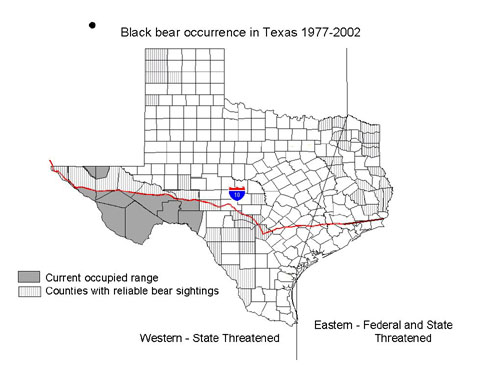

The bear-vehicle collision took place on Highway 90, about 1.5 miles south of Comstock in Val Verde County. The 69 pound, sub-adult, male

The bear-vehicle collision took place on Highway 90, about 1.5 miles south of Comstock in Val Verde County. The 69 pound, sub-adult, male