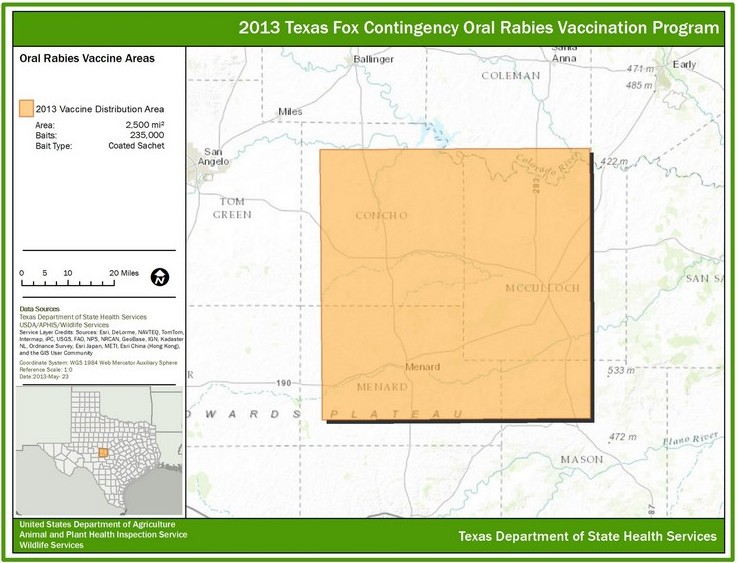

The rabies virus poses a serious threat to Texas wildlife and people that spend time out of doors. Hunters are especially prone to running into animals that are infected with rabies. A case of Texas fox variant rabies was found near the Concho/McCulloch County line. This variant of rabies is of special concern to public health officials. A contingency wildlife management and disease response is being implemented to try and prevent it from spreading to other counties. A protocol has been developed to help agencies respond to calls about potentially rabid wildlife, and to facilitate the testing of animals suspected of having rabies.

According to state wildlife and disease officials, Wildlife species of most concern in Texas fox variant rabies transmission are foxes, coyotes, bobcats, raccoons, feral or free ranging dogs and cats and livestock. Any mammal, including white-tailed deer and feral hogs can contract rabies., but they are not of great concern to the variant of concern. An animal is considered suspect if it is a member of a species of concern and is aggressive, unafraid, acting unusual.

- If a suspect animal is found in the target area (refer to a listing of counties on page three or the map on page four) please contact appropriate personnel in those areas (Animal Control, Sheriff’s Department, local County Trapper, Texas Parks and Wildlife-Game Warden) to have the animal humanely destroyed. Refer below for pick- up and rabies testing.

- If a private citizen in any of these counties is witness to a suspect animal and cannot contact appropriate personnel it is asked that the animal be humanely destroyed and held until appropriate personnel can be contacted. This recommendation pertains to citizens living outside of the city limits.

- State officials ask that all safety and care be practiced when attempting to obtain suspect animals. Remember: always wear latex, rubber or leather gloves when handling dead animals.

Human/Domestic Animal Rabies Exposure

If a human or domestic animal has been bitten, scratched, or otherwise potentially exposed to rabies by a wild or domestic mammal, or if there is any question about what constitutes exposure, contact the Texas Department of State Health Services. If located in West Central Texas, contact Dr. Ken Waldrup at 915-834-7782 or 915-238-6216; or call Kathy Parker at 432-571-4118 or 432-230-3007. For after-hours rabies emergency cal 512-776-7111. Contact the Health Department at 915-834-7782 or 432-571-4118 if there is a question of rabies exposure.

Rabies Suspected – Sick or Strange-Acting Animals, or Animals Found Dead

If personnel are available, the following agencies will provide assistance or advice on how to deal with a sick-acting raccoon, bobcat, fox, coyote, feral dog or cat. Contact Health Region 9/10 offices of the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) during normal business hours (M-F, 8-5). If in West Central Texas call Dr.Ken Waldrup or Kathy Parker. Additional Contacts include the Texas Wildlife Services Program (TWSP). You can call the closest office: San Angelo at -325-655-6101, Brownwood at 325-646-4536, Kerrville at 830-896-6535, Uvalde at 830-278-4464, or if no response, contact the central office of Texas Department of State Health Services Zoonosis Control at 512-776-7255 or the TWSP State Office at 210-472-5451. If no other options are available, keep pets and children indoors and leave the animal alone.

Note: State officials are actively trying to test suspicious foxes, coyotes, bobcats, and raccoons for rabies. Freezers are located at several Texas Wildlife Services offices. Freshly killed or dead animals should be kept cooled or frozen for testing. Do not shoot animals in the head. Contact one of the above telephone numbers for handling procedures.

No Rabies Exposure, But Nuisance & Injured Wildlife/General Wildlife Information

For information on Oral Rabies Vaccine (ORV) baiting and Enhanced Rabies Surveillance (testing), contact the Texas Department of State Health Services’ Dr. Skip Oertli at 512-776-3306 or Texas Wildlife Services Program’s Bruce Leland at 210-472-5451. TWSP can also provide advice on preventing and resolving nuisance wildlife problems.

Enhanced Rabies Surveillance Counties of West Central Texas

- Brown

- Coleman, Concho

- Gillespie

- Kimble

- Llano

- Mason, McCulloch, Menard, Mills

- Runnels

- San Saba, Schleicher, Sutton

- Tom Green

Rabies Prevention: Things you can do to protect yourself, your family and your pets

- Do not feed, touch, or adopt wild animals, and be cautious of stray dogs and cats. Rabid animals do not always appear ill or vicious.

- Teach children to leave wildlife alone. Be sure your children know to tell you if an animal bites or scratches them.

- Call your doctor and your local health department for advice if an animal bites or scratches you. Thoroughly wash the wound with soap and water and report the incident immediately!

- Have your veterinarian vaccinate your dogs, cats, or ferrets against rabies. Keep pet vaccinations up-to-date.

- Tightly close garbage cans. Open trash attracts wild or stray animals to your home or yard.

- Feed your pets indoors; never leave pet food outside as this attracts wildlife.

Also, do not relocate wild mammals – this can cause rabies to spread quickly to new areas. Importation of rabies-vector wildlife into Texas from other states or other counties would be disastrous. Landowners and homeowners should not transport and release animals.